Tim MalcomVetter

Co-Founder / CEO

Free the Statue

There is a famous quote that is often attributed to the great renaissance sculptor, Michelangelo:

Michelangelo’s exact quote from a letter to Benedetto Varchi in 1549 was “io intendo scultura, quella che si fa per forza di levare,” which translated to English means: “By sculpture I mean that which is made by the force of taking away,”, i.e. sculpture is subtraction.

Michelangelo’s contemporary, Leonardo da Vinci (although not a sculptor) also corroborated this concept of sculpture as subtraction in the 1540s:

The sculptor’s art consists of taking away from the stone whatever is not needed, in order to set free the forms that are imprisoned in it.

#What does this have to do with cybersecurity?

Everything.

A few years ago, but within days of each other, I witnessed a security telemetry setup at two different companies that, solely based on my prior experience, gave me immediate cause for serious concern: EDR was being sent to a customer’s SIEM and only forwarded to a third-party MSSP’s managed SOC when the data matched rules curated by the MSSP. The problem that I recognized wasn’t technical as much as it was economic: the incentives-to-resources were misaligned, and I knew ransomware would be the result.

It didn’t take long. Both companies, in a manner of a couple months, had ransomware hit them, ironically, about a week apart. The first company took all of their WAN connectivity offline for a whole week and avoided paying the threat actor, but the loss of productivity and recovery was massive. The second company wasn’t as lucky and paid the ransom to decrypt their files and recover their business.

In what I have since written off as a case of Stockholm Syndrome, the first company stayed with their MSSP. (I would have fired the MSSP if I worked there.) The second company, having paid the ransom, didn’t hesitate to fire the MSSP and pick a new provider, as they should have.

#They should have listened to Michelangelo

In both companies, the telemetry capture and review process followed the opposite of the Renaissance sculptors. The MSSP didn’t remove the excess to reveal the unseen signal inside. Instead of subtraction, they attempted addition (but in actuality added nothing but risk). The MSSP believed their “threat-informed defense” SIEM rules would add to the already high-fidelity signal. To complete the analogy, they were attempting to glue statues to the outside of a jagged, unrecognizable chunk of marble.

Both victim companies were smaller, so they didn’t make major news headlines. Nobody, except those involved, will remember these stories today, let alone 500 years afterwards like Michelangelo’s statues are remembered today. In fact, those involved will remember it as the opposite of virtuous art!

I’ll remember it as a lesson.

#Recognizing Incentives

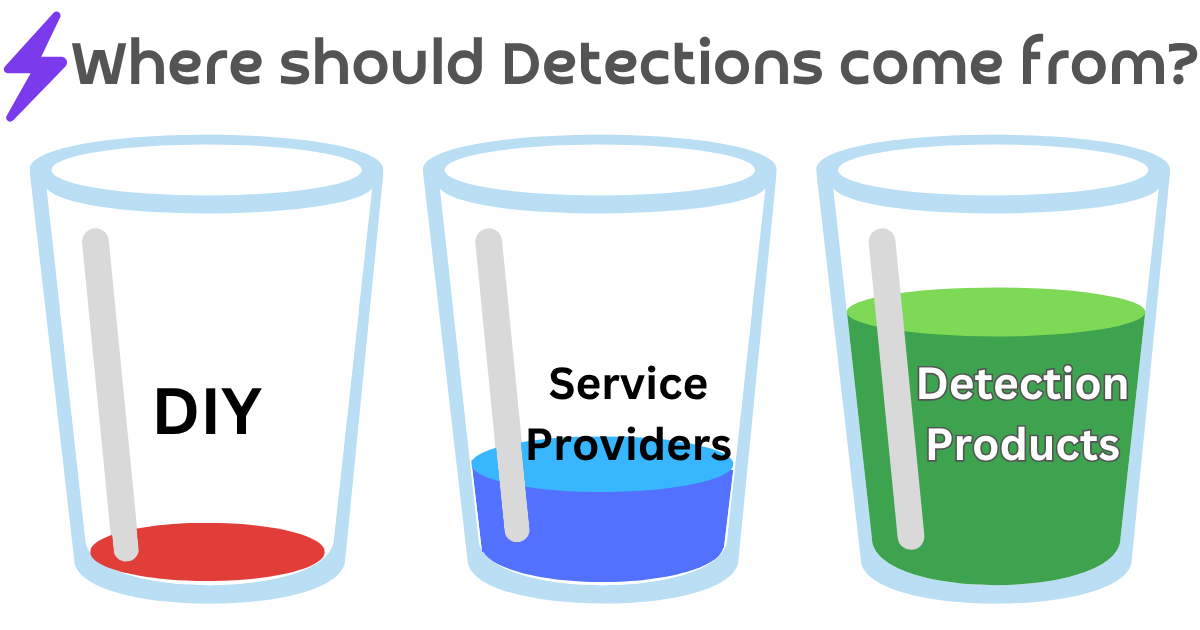

The single most important concept to learn in security is the power of incentives. Whole volumes should be written about this topic! In the story of these two companies, which always makes me recall Michelangelo’s quote, the incentives that needed aligning were the creation and processing of detection content. For reference, we previously discussed where detection content comes from:

- Detection Product Vendors

- Third-Party Service Providers

- DIY (a company’s internal) Detection Engineering

All three sources can build a large quantity of detection content. Maybe given enough years (or lifetimes), all three sources could eventually cover all the important detection scenarios, but they’ll get there at much different speeds. We should expect the quantity of detection content should come in precisely the above order:

- A product vendor can build once and deploy as far and wide as its commercial reach allows.

- A third-party service can mostly do the same, but it takes more labor per deployment, so its reach is more expensive, and therefore not as fast to penetrate the market.

- Lastly, internal teams lack the time and resources to keep up, save a few really large companies (and even they can’t match the speed of product vendors).

#Applying the Understanding of Incentives

I knew in the story of the two companies above, that the detection content coming from the EDR vendor would iterate and change faster than the SIEM detection rules the MSSP deployed to capture and forward important endpoint detections to their SOC … no matter what they said! I didn’t have to see the details of what they built to know this, I just had to understand their intent (to filter noise from reaching their SOC as far upstream as possible to minimize cost) and which party had the better incentives to stay engaged (i.e. the EDR vendor, not the MSSP).

The cost would ultimately be ransomware.

Product vendors have the economies of scale to change their content most often and rarely will the output of these tools have version control, i.e. the service provider has to be on the active lookout for changes to schema and metadata. This means the service provider’s downstream logic to identify and forward the most important events is brittle. One change upstream, and signal is missed downstream. In the case of these two companies, the data from the alerts, including the title, metadata fields, and in one case even the index in the SIEM locating where to search for it, had changed without the incumbent MSSP’s knowledge.

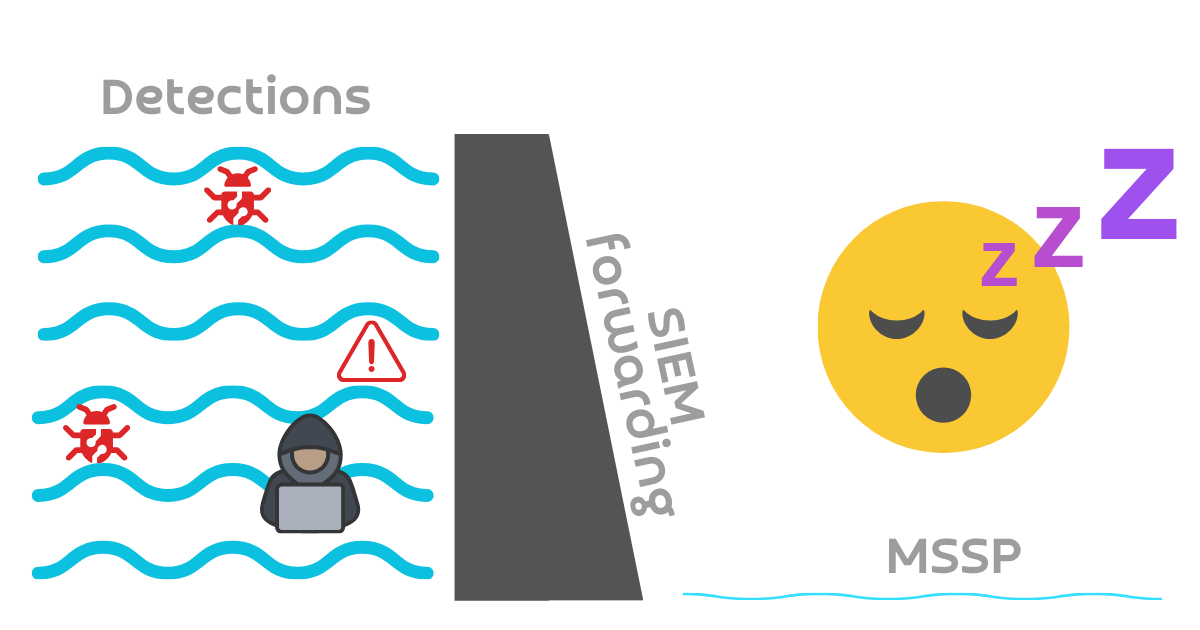

#The SIEM became a dam

The data version synchronicity issue, as a result of the misunderstood incentives, resulted in the pooling of telemetry, not the flowing of it to the third-party SOC. The SIEMs became dams, holding back the flow of telemetry.

Or to say it another way common in cybersecurity: these MSSPs failed closed. When the alert-forwarding rules failed, the flow was closed off and nobody saw the attacks.

#The Wirespeed Approach

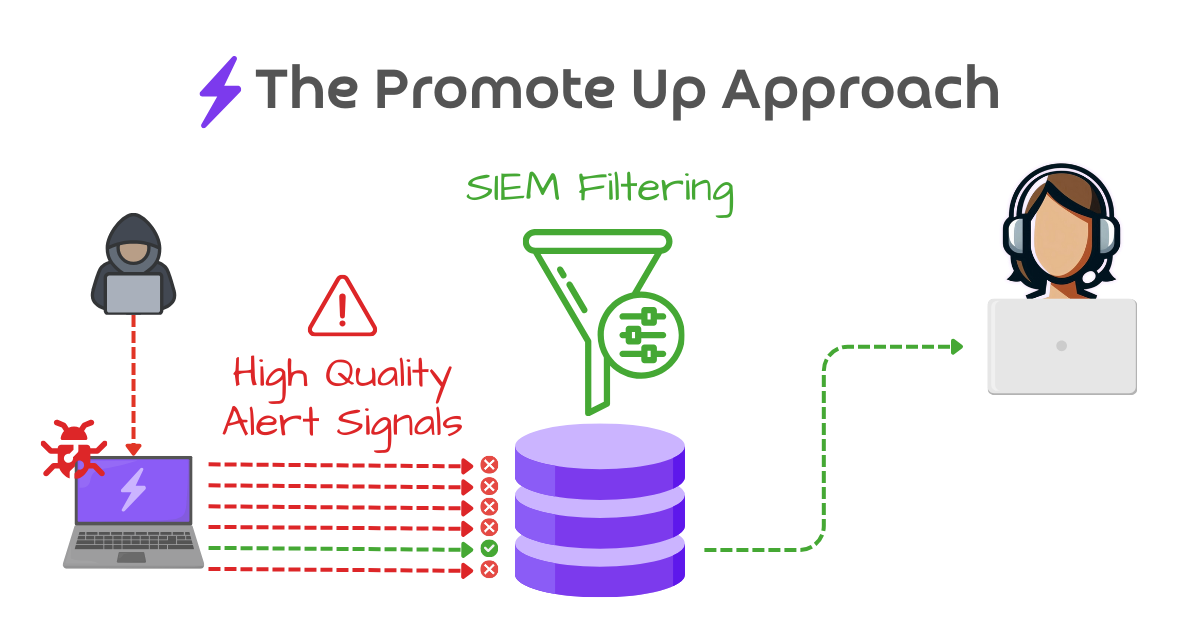

We follow Michelangelo’s mantra: the beautiful, valuable statue signal of a threat actor is buried inside the large block of marble (the total volume of telemetry). Rather than promoting up signals we think are valuable, we knock down signals we know are not, like this:

This ensures that we are not tightly coupled and brittle with our upstream detection sources at our customers. When a detection vendor changes something and it slips through our primarily deterministic approach to triaging detections, we err on the side of taking action. If it’s a false positive, especially because of a change of output from the vendor’s tooling, we re-calibrate and move forward. We never fail closed. We fail open.

When we couple our approach to Quality Assurance with our intense focus on minimizing False Positives, our supervisory-human-in-the-loop approach ensures we have the tightest possible tolerances for error at scale, and our customers stay safe and protected.

Want to know more about Wirespeed? Follow us on LinkedIn / X or join our mailing list.